Violent clashes between workers and industry intensify

In the years leading up to the first World War, increasing tensions between workers and management led to strikes and violent protests across several industries. In 1892, at least three company guards and seven workers were killed during the Pennsylvania Homestead Strike as management of the Carnegie Steel company attempted to break a workers union.

In 1914, a violent attack on striking miners by guards of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company–whose largest shareholder was John D. Rockefeller–resulted in the deaths of several miners and their families, including two women and eleven children. The attack, known as the Ludlow Massacre, was the deadliest incident in the year-long Colorado Coalfield War that grew into a nationwide scandal for the Rockefeller family.

Rockefeller’s views on industrial relations evolve

At the beginning of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company strike, Rockefeller wrote to the company’s management to express his support for suppressing the strike. In testimony before Congress after the Ludlow Massacre, however, he advocated for the “open shop” principle that would allow, but not require, workers to join an outside union.

Later, after the Congressional Commission on Industrial Relations released a damning indictment of Rockefeller’s role in the Ludlow Massacre, Rockefeller began a more concerted effort to address the mounting crisis for both his businesses and his public image, hiring the labor experts Clarence J. Hicks and W.L. Mackenzie King to help develop the Colorado Industrial Plan that created a model for company unions with elected employee representation.

The Treaty of Versaille calls on nations to address the “labor problem”

The Treaty of Versaille, which officially ended WWI, established the International Labour Office of the League of Nations (later called the International Labour Organization). In the preamble to the new organization’s constitution, signing countries expressed the threat to global peace posed by inadequate worker protections, writing that:

“...conditions of labour exist involving such injustice, hardship,and privation to large numbers of people as to produce unrest so great that the peace and harmony of the world are imperilled; and an improvement of those conditions is urgently required.”

Protests continue as economic conditions deteriorate

During the depression of 1920-1921, wages in many industries dropped by half, and national unemployment grew from an average 5.2 percent to 8.7 percent. Then, in the summer of 1921, more than 100 people were killed during the Battle for Blair Mountain after coal companies in West Virginia sought to prevent miners from joining and organizing with the United Mine Workers. The violent clash ended only after intervention by the U.S. Army.

Clarence Hicks visits Princeton–and proposes a new academic endeavor

After being hired by Rockefeller to address employee representation issues at the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, Clarence Hicks–a longtime industrial relations specialist–was appointed the director of industrial relations at Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company in New Jersey. It was in this role that Hicks was invited to Princeton to speak with students about labor relations policy.

During his visit, Hicks had the opportunity to tour the Pliny Fisk Library–a donated collection related to the financial history of American corporations–where he met students studying the information and had an idea: What if companies could also contribute corporate information on labor relations?

Announcement of Hicks's visit in the Daily Princetonian, Volume 42, Number 169, 20 January 1922

IR Section is formed with initial funding from John D. Rockefeller

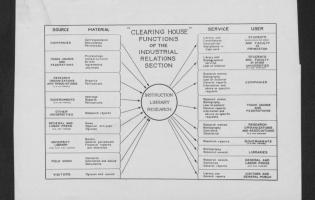

At a dinner with faculty hosted by Princeton President John G. Hibben, Hicks outlined his vision for the IR Section as a subdivision of the Department of Economics where students and faculty could build and maintain a unique library of data and information to inform their academic study of labor issues. Under Hicks’ proposal, this library of information would be available not only to faculty and students, but also labor leaders, business leaders, and anyone else who would want to access it. Rockefeller himself provided the funding for the Section’s first five years.

Find “My Life in Industrial Relations” at the Princeton University Library

"Independence is a critical source of strength"

"In a field in which big government, big industry, and big unions promote conformity within their own organizations and exercise powerful persuasion upon those who would influence policy, independence is a critical source of strength."

"The Industrial Relations Section of Princeton University in World War II. A Personal Account by J. Douglas Brown.” (The Industrial Relations Section, 1976)]